Xenix 2.2.3c Restoration: No Tools, No Problem (Part 2)

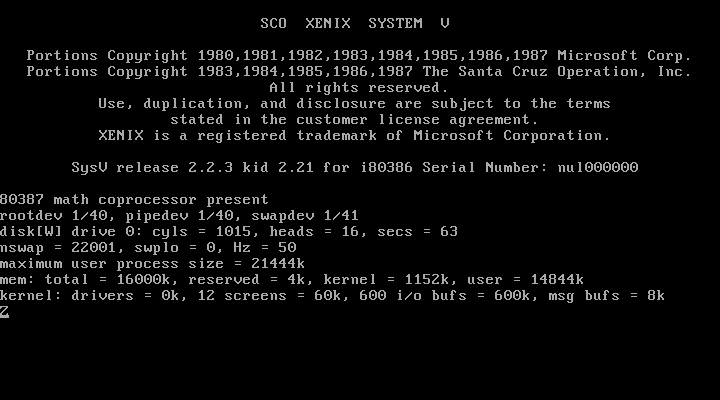

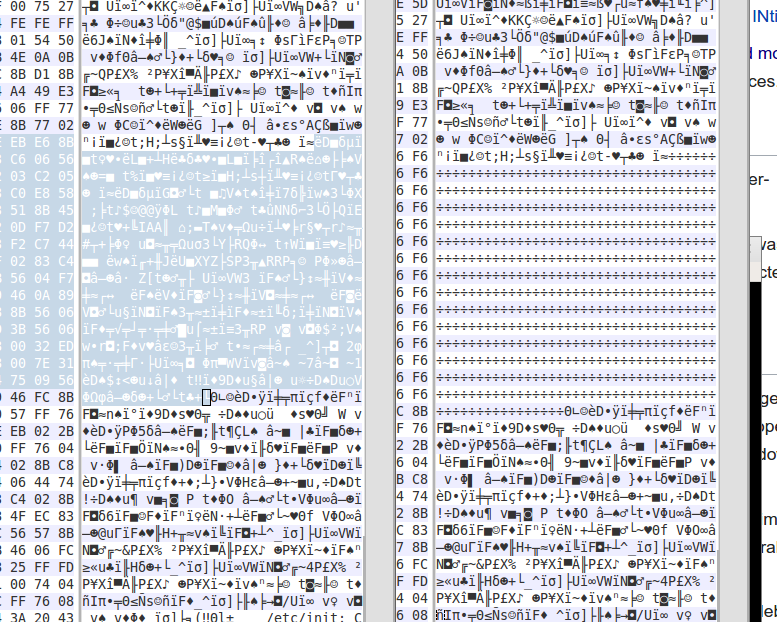

When we last left off, with the help of the excellent Michal Necasek of the OS/2 Museum, we had gotten the damaged Xenix 2.2.3c past the first hurdle of installation, and directly into a post-reboot crash, the cause of which (at the time) I suspected was another emulation failure.

Needless to say, I needed to get past this. At this point, I have been examining the raw images as best I can, and figuring out how the installer comes together. After a few experiments, I managed to determine a few basic facts about how Xenix is installed when booting from N1/N2:

- Coming out of reset, the Xenix kernel loads from N1, prompts for the "filesystem floppy" and starts /etc/init or

/etc/inir coming out of IPL

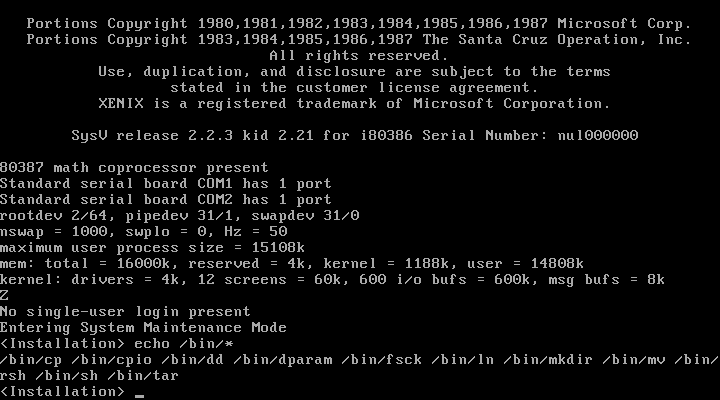

- Init prints the "Entering System Maintenance Mode" line.

- Inir is used for running fsck, if necessary. Afterwards, it starts init.

- Initially, the system starts /usr/lib/mkdev/hd which does the following

- Format the Xenix partition, create slices, and mount the hard drive under /mnt

- Compile the keyboard configuration files so the language selection sticks past reboot

- Create a few device nodes manually

- Cpio is used to copy a list of files from N2 to the root partition.

- /profile.hd is copied to /mnt/.profile

- Install a boot sector to the MBR of the hard drive and configure the bootloader for HDD booting

- The hd script does the initial language selection, followed by fdisk

- After the completion of the script /.profile is run as the system tries to bring up the root prompt which reboots the system after prompting that N1 should be re-inserted after the boot prompt.

So with knowing what the installer is trying to do, it was time to try and get down and dirty with it.

Have /bin/sh, Will Travel

With a relatively complete understanding of the initial installation steps. I decided to create a boot floppy. By finding the initial strings for language selection, I was able to find where in the boot image the installer starts, and force it to pop open a dedicated shell with a hex editor. With that in place, I finally had a chance to explore the system somewhat. I learned a few interesting details while digging through this. There are references to 96 and 135 tpi media such as the following.

# We want to make the hard disk bootable in the 96 and 135 tpi # installations so that we don't need to re-insert N1 to re-boot

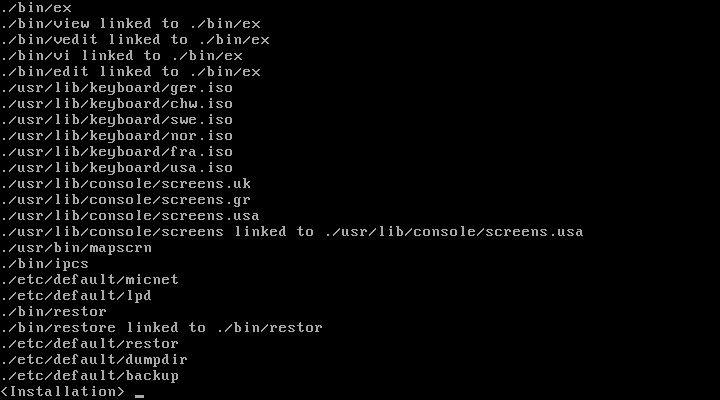

TPI refers to as "tracks per inch" and is a very old style way of referring to differing types of floppy disk medium. In this specific case, 96 TPI refers to low- (or double-) density 720 KiB 3.5-inch floppy disks, and 135 TPI refers to high-density 1.44 MiB floppies. This suggests that this version of Xenix was available in multiple types of media. This comment would help me immensely in trying to perform a manual install. As it turned out, much to my annoyance, the N2 file system was extremely lean overall. By using "echo *" as a poor-man's ls, I was able to get a list of what I did and didn't have, the /bin directory was rather ... empty.

I also found I had /etc/mount and /etc/mknod which helped, but not much overall. Deciding to charge ahead, I ran through the normal partitioning and formatting steps, and then rebooted again with N1, and my modified N2 boot floppy. As I got my hands dirty, I also began to unpack and explore the other disks. As I mentioned before, aside from the first two disks, all the other ones were simply tar archives written as raw files. Or more specifically:

$ file *.img Basic Utilities 1.img: tar archive Basic Utilities 2.img: tar archive Extended Utilities 1.img: tar archive ...

Each disk begins with a specific header with an empty file which identifies the disk number, product set, and machine set:

./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=386AT/rel=2.2.3c/vol=N03 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=386AT/rel=2.2.3c/vol=N05 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=386AT/rel=2.2.3c/vol=N04 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=386AT/rel=2.2.3c/vol=N06 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=n86/rel=2.2.2c/vol=B01 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=n86/rel=2.2.2c/vol=B02 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=n86/rel=2.2.2c/vol=X01 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=n86/rel=2.2.2c/vol=X02 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=n86/rel=2.2.2c/vol=X03 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=n86/rel=2.2.2c/vol=X04 ./tmp/_lbl/prd=xos/typ=n86/rel=2.2.2c/vol=X05

As one can plainly see, the B/X disks have a slightly different version, and identify themselves as n86, or generic x86. Furthermore, the N disks are the only ones that have "80386" binaries as defined by their headers. On top of that, investigating N1 I found a master manifest file that lists all the files on all the base installation disks, as well as special files, and mknod numbers. Bingo. Almost all the pieces I needed.

A quick check of the manifest file listings, and the contents of each disk confirmed that despite the differing version numbers, the media in and of itself belonged with each other; that is, these are the disks that correspond to Xenix 386 2.2.3c.

Dealing With Floppy Disk Controllers, Media Controllers, and More

My initial experiments taught me a few things about Xenix, chief of which it very much didn't like its root filesystem floppy removed. If I removed N2 from A: at any point, Bad Things™ would happen not long after. As such, if I wanted to successfully bypass the installer and extract things into a working system, I need to figure out how to talk to it.

On UNIX systems, for those less familiar with them, disk operations are handled by special files in the /dev directory, such as /dev/hd0 for the first hard drive, or /dev/fd0 for first floppy drive controller, and so on. In contrast to more modern Linux systems using udev, these nodes exist as a set of static "dummy" files, created via the mknod command — mknod takes four arguments; the file to create, whether the device is binary or character based, and a blank-separated major/minor number that associates it with a driver in the kernel. Combined with the manifest file, it should have been trivial to create /dev/fd1 if it weren't for two simple issues.

- It didn't work correctly

- Xenix and read-only root filesystems really hate each other

As far as I can tell, having a read-only root filesystem is a hack that essentially is in place for two things; checking the file system and installation. Under Xenix, when / is mounted read-only, write operations succeed, and for a brief moment, you'll see a file in place and can even interact with it for a time and then it vanishes. Hindsight being 20:20, I could have simply forced / to be mounted read-write, but at the time, the thought didn't occur to me.

Needless to say, this caused all amounts of fun. I eventually realized I could simply mount the root partition at /mnt, and create the device nodes I needed at /mnt/dev, and they would stick around. First hurdle passed!

The floppy issue was a bit more difficult to work out. During installation, the scripts read from the /dev/rinstall device. The manifest also listed /dev/rinstall1 file which also generated errors. The manifest listed several variations.

FD48 b666 bin/bin 3 ./dev/fd1 2/5 ./dev/fd148 ./dev/fd148ds9 FD96 b666 bin/bin 1 ./dev/fd196ds9 2/37 FD96 b666 bin/bin 2 ./dev/fd196ds15 2/53 ./dev/fd196 FD96 b666 bin/bin 1 ./dev/fd196ds18 2/61

In practice, the only node that would work correctly was /dev/(r)fd196ds9, which probably means nothing to most people. Broken down, it's a mode selection for fd1 (B:). 96 refers tracks-per-inch, ds for double sided, and 9 for tracks per side. AKA, mode geometry for low/double density 3.5-inch floppies. Having divined the correct setting, tar could now read the disks:

Feeding the disks through tar, and manually executing several of the installation steps gave me a reasonable approximation of what the installed system should look like. Testing many of the utilities confirmed my original suspicion that the vast majority of the data was intact. Furthermore, I managed to extract /usr/bin/chroot from the Extended Utilities disk.

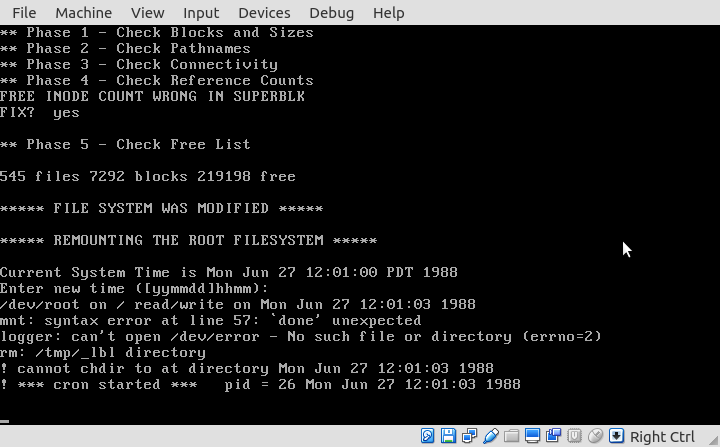

To make a long story short, I successfully extracted all the base installation disks, and began to work out the necessary steps to boot from the root file system. The system was extremely unstable in this state, with several utilities causing immediate kernel panics on launch (most annoying, vi did this, forcing me to use ed for almost all file editing). After several attempts, using N1 as a boot floppy, and pointing the root argument to the HD, I got very close to a successful boot.

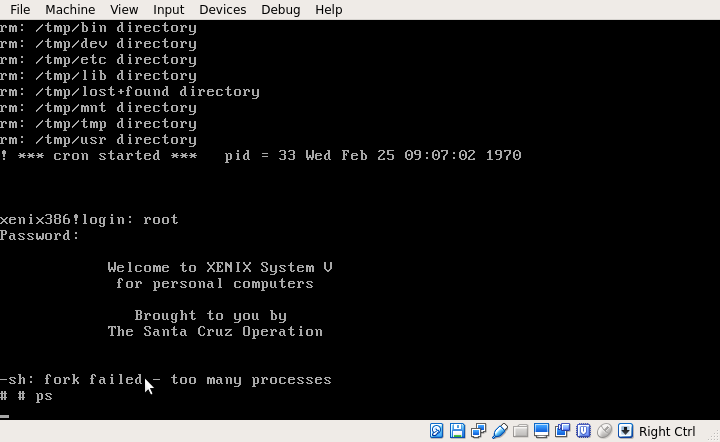

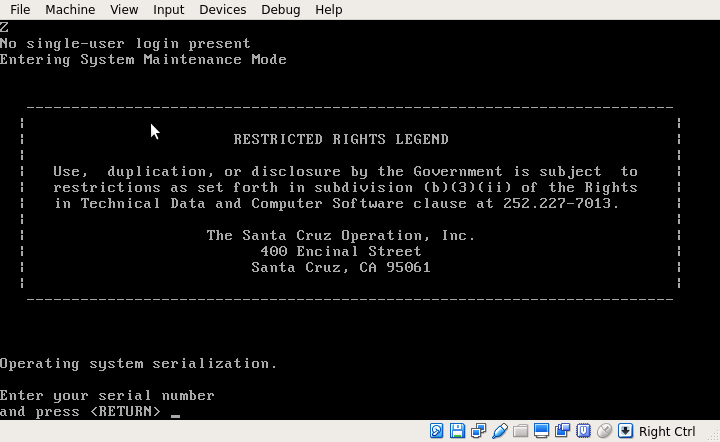

The important line to see here is *** cron started ***, which is one of the final steps listed in /etc/rc before bringing up the login prompt, and a very optimistic step at eventually getting this all working. At this point, I had also learned the existence of the /tmp/init.* files, special shell scripts run during installation. Through these, I managed to learn of the setperms command, which reads the master manifest files on N1 and other disks, and does final tweaking and configuration. I also learned that I needed to do a brand operation on /etc/getty to decrypt the file, and install a serial number in it. With chroot in hand, and fingers crossed, I ran setperms with each manifest, rebooted, and ...

30 Years of Copy Protection

Well isn't that an interesting problem? That's the type of message you'd expect if someone detonated a fork bomb on your system.

Another examination of the installation scripts revealed the problem. During installation, three files are personalized with the "brand" utility. In the case of /etc/getty and /usr/sys/lib/libmdep.a, these files are decrypted with a secret derived from the serial number, and activation key. It would also foreshadow the issues we ran into once we began trying to restore the media to near-mint condition. The brand utility is also used to write those values into the kernel binary image.

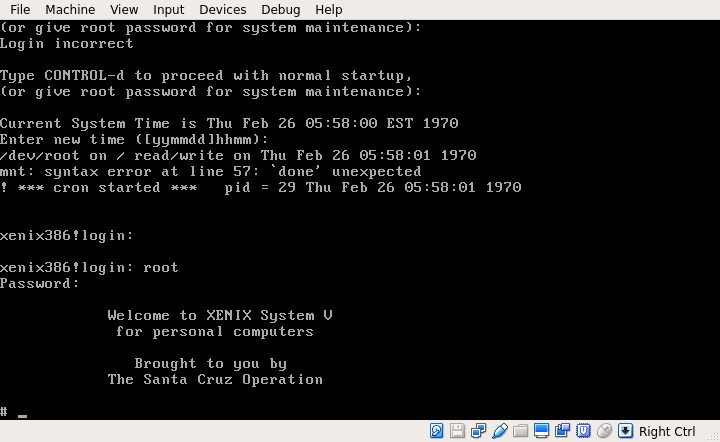

As I found out as part of debugging, Xenix has unique behavior in handling the validation of serial numbers depending on how it's started. By its nature of being essential boot code, the kernel, by definition, can not be encrypted. As such, the kernel has a runtime check to make sure it has correct information. When started from the hard drive, the kernel reports "Invalid Serial Number" if it gets a mismatched set of keys and subtly degrades behavior.

However, in my case, my frankensteined system was loading its kernel from the the floppy drive. In this case, Xenix suppresses the serial check and prevents the message from displaying, but doesn't prevent the tripwire from being activated.

The tripwire in question is drastically lowering the number of processes that can be run. As it turns out, the limit is reached when the system is brought up in multiuser mode. As I found out (much) later, this behavior is actually documented as a footnote in one of the Xenix 286 manuals. As such, I copied the kernel from N1 to the hard drive, personalized it with brand, and after a reboot ....

Victory.

With some more fiddling, I was able to run most of the post installation scripts, and even load the package manager, though it had some corruption issues.

Swiss-Cheese

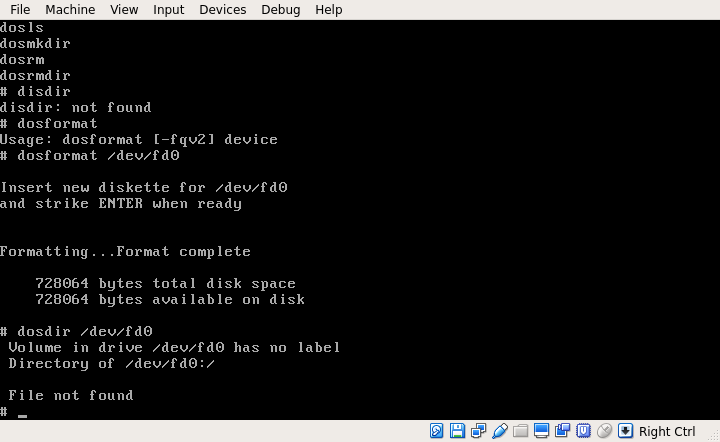

Right about this time, Michal got back to me, and found that the reason the system hangs after reboot; N2 was missing two sectors in /bin/init. I was somewhat in disbelief, so I pulled out dosformat, made a DOS compatible disk, and copied out /etc/init from the booted system.

Sure enough ...

Ugh. So my frankensteined system was booting with half of its init binary missing. Awesome. At this point though, I had noticed something interesting on the international supplement, specifically, a /etc/init8 binary, one that had the same file size as the file on N2. When I compared them side by side...

Well isn't that interesting! A comparison of file-sizes show they're identical length, with similar (though not identical) modification dates. As far as I can tell, the only modification appears to be the time-stamp further in the binary. On a hunch, I compared the tail ends of the missing sectors, and they matched. So I simply copied the missing blocks from init8 to init, and then started a fresh new VM. After feeding floppies, this time, instead of the dreaded Z, I got something new.

It would die shortly afterwards, but now I was on a mission to try and see if I could restore the media to working state. I already proved to myself that enough data existed to at least make a restoration attempt viable. However, to rebuild the media, I needed to characterize the existing damage and find a way to rebuild or replace the missing sectors.

Next time, we dig into the world of teledisk, data reconstruction, and our first steps towards restoring the media.

~ NCommander

Note: This post originally appeared on SoylentNews on March 8th, 2017